Do we need to ban drones used for recreational fishing?

In recent years the use of drones for recreational fishing purposes has dramatically increased, raising ethical concerns amongst fellow anglers, potential privacy and safety concerns amongst the public, increased conflict between fisher groups, as well as having deleterious effects on the targeted fish species and other animals that inhabit the near shore coastal zone. Given the recent development of the practice, a consortium of researchers from Rhodes University, the University of Cape Town the Oceanographic Research Institute in South Africa, used unconventional data sources, such as social-media analyses and google trends, to understand the extent of the practice globally. We found that sharks are particularly susceptible to capture in the South African drone fishery, which does raise potential concerns as many of these species are threatened. While we could not find any legislation directly regulating drone fishing globally, the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries and Environment has recently issued a public notice banning the practice in South African waters.

Should we be moaning about droning?

The use of unoccupied aerial vehicles (or drones) within our daily lives is fast becoming the norm rather than the exception. Their development has primarily been driven by the military, but more recently and primarily due to advances in the miniaturisation of lithium-ion batteries, drones have become small and available for a multitude of commercial and consumer purposes. They are being developed by large retailers as delivery vehicles or used by extreme sportsmen and the film industry to get cheap aerial footage. The options are almost endless and if you need an eye in the sky or a platform to carry a payload or sensor, a drone is probably your answer.

While their use is becoming common practise within our daily lives, there are certain socioecological concerns that are beginning to reveal themselves. Socially the majority of our concerns are around privacy or relating to the chance that a drone may fall out of the sky and land on our head. While these are worthy concerns which means that in some regions, drones are quite heavily regulated, their impact on wild animals seems to be less regulated, despite a body of evidence suggesting that drones are something to worry about. Birds seem particularly vulnerable, with ravens, seagulls and eagles are all known to attack drones in certain circumstance. In one case, a drone crashed within a colony of thousands of seabirds, resulting in the entire colony abandoning their nests. It is, however, not only the disturbances caused by drones that effect animals. Drones are also beginning to be used to increase the harvest efficiency of both hunters and fishers to either find their quarry in both instances or be used to carry baited lines to areas out of reach in the latter.

While some fishermen are enjoying the advantages of drone use, there has been much ethical debate regarding the implication of drone fishing globally and along the South African coast. A group of South African researchers recently decided to investigate this phenomenon that is taking shore-based angling by storm in South Africa. We can’t deny that with the use of drones to drop baits further offshore and the simultaneous use of stand-up big game tackle, that anglers can now catch some really big, magnificent sharks and fish from the beach, an activity that was previously only possible from boats. Drones have allowed anglers to drop their baits onto reefs or sandbanks out of the reach of ski-boats and conventional casting shore anglers. If they were not so effective, drones would not be so popular amongst anglers.

So why worry if recreational fishers are becoming better at catching fish? The issue is that recreational fishers are considered “self-subsidised”: regardless of the amount of fish recreational anglers catch, their motives to fish are not driven by profit or catch, which is the case for most commercial or small-scale fishers, but by pleasure (read: Kleiven et al. 2020). This may sound weird, but it means the recreational fishers will continue fishing even if there are very few fish left – which is not the case with commercial or small-scale fishers who will stop fishing when catch rates become too low to make a profit or support their families. So, if recreational fishers are fishing for fun and catch rate does not determine whether they fish or not, any increase in their fish catching ability can have significant effects on the fish stocks they catch. Furthermore, the number of recreational fishers is rarely controlled in most countries: all you need to do to go fishing is to buy fishing license. Therefore, unlike commercial fisheries, which are generally quite regulated, the number of recreational fishers globally is always continually rising. So, if this number of fishers continues to rise –which it is, and they continue to become better at catching fish – which they do, then we potentially have a problem on our hands. As a result, in certain regions recreational fishing techniques are regulated: for example, the number of hooks an angler is allowed to use on a line, or the use of nets or longlines, which are often used by commercial fishers are generally prohibited. But more recently there has been a call to limit the numerous technological advancements that have recently began to spring up (read Cooke et al. 2021)

So what did our research find?

(see Winkler et al. 2022)

Trying to gather information and data on such a new angling technique proved to be quite a challenge. Initially the researchers scrolled through social media pages such as Facebook, Instagram and YouTube looking for drone fishing-dedicated groups, evaluating the size of these groups and when they were first established. Understanding when drone fishing first started to become popular amongst anglers is important so that we know how long fishers have been using drones. The first dedicated Facebook groups began to appear from 2015–2017, suggesting that this is potentially the time at which the practise started to become popular. But why did it take so long? Drones have been around for a while. Was it just a coincidence? Did someone release a dedicated fishing drone for sale around this time?

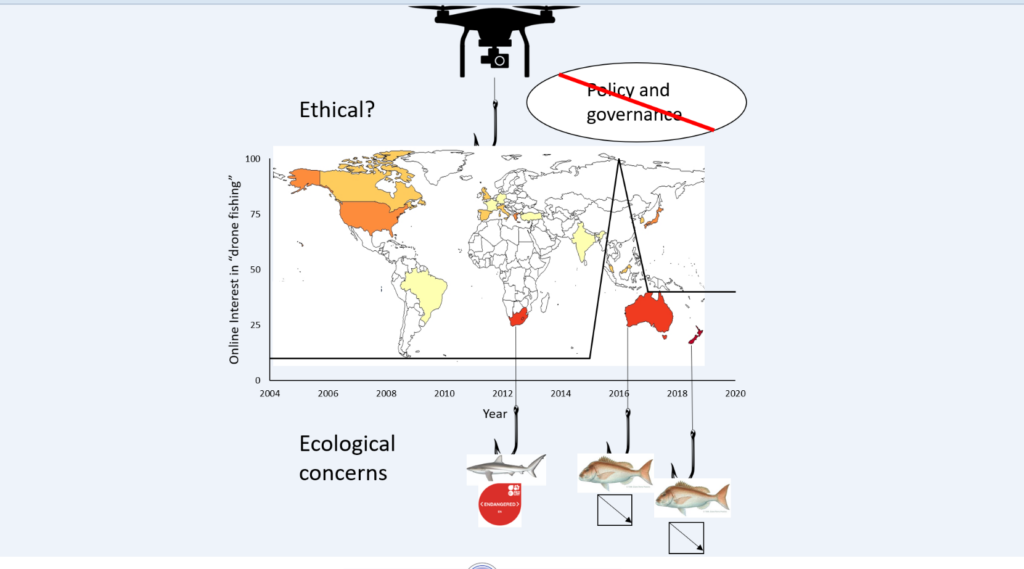

To try and find out exactly when drone fishing became popular, we used a tool provided by Google called Google Trends, which basically monitors internet search term volumes for a specific search term over time and for a specific region. So, we investigated when people started to search the internet using the term “drone fishing” and then looked at which countries searched the internet the most to get an idea of when popularity increased and where it is searched the most. Our findings were very interesting. We found that global online interest in drone fishing spiked in May 2016 and after that internet search interest increased by 3.5 times or 357% from levels before the spike in May 2016. So, what happened in May 2016? At that time a very popular YouTube video was released of an angler catching a big longfin tuna from the beach in Australia using a drone. So basically, we found that a viral YouTube video seems to have been the catalyst to get people interested in drone fishing. So which countries searched the internet using the term “drone fishing” the most? In first place it was New Zealand, followed by South Africa and then Australia and to a lesser extent, Japan, the US, and Greece.

Then we asked: what fish species do these drone anglers target in these countries? Are they targeting fish of conservation concern or are they using drones to fish sustainably? To get an idea of what was being caught, we decided to again use freely available online data, available by watching 100 YouTube videos posted by drone fishermen in the three countries where online interesting into drone fishing was the highest. Both in New Zealand and Australia, red snapper was most frequently observed catch. While red snapper is not a species of direct conservation concern, recent data does suggest that population declines are occurring. In South Africa, the results were quite different, with sharks making up the majority of the reported catches online.

Should we be worried?

The short answer in our opinion is yes, we should be, but more research into the effects of the widespread use of drones by shore anglers does need to be investigated. We also need to look at the issue holistically and evaluate how the use of drones maybe affecting the targeted fish themselves, the environment or habitats in which these fish are found, the impact on other animals that inhabit the coastal zone and importantly the other people that utilise the coastal zone, not just drone anglers. We term this the socio-ecological system – essentially the entire system that is potentially affected from people, the fish that drone fishers target, as well as all the other factors that make up the natural world in which the practice may affect.

Potential socio-ecological effects of drone fishing

Drones with cameras allow anglers to identify ideal fishing habitats or shoals of fish far from the shore. These areas are often too far to reach by casting from the shore, but are still in the active surf zone making them dangerous for boat anglers. These areas have thus provided an element of refuge for certain fish species and being able to now target them with drones will place them under greater fishing pressure. There are, however, also limitations to the use of drones, such as the weight of the equipment, which reduces angler mobility and the reduced capabilities of drones in windy conditions (although the technology is improving rapidly).

Although the effects of drone fishing on fish stocks is obviously greatest when the targeted fish species are captured and killed, a substantial proportion of recreational catches are released. This is because recreational angling often makes use of catch-and-release to comply with fishery regulations (i.e. bag and size limits) or to promote the voluntary conservation goals of anglers. Additionally, certain trophy species are not desirable food-fish and are therefore almost exclusively released (e.g. large sharks and rays). Regardless of the reasoning, it is critical that released fishes sustain minimal ill-effects and display maximum rates of survival. Numerous studies have shown that longer fight times can increase the post capture survival of fishes and given that drone fishers often hook their catch many hundreds of meters offshore, there is a high probability that these fish maybe less prone to survival than if they were conventionally caught. At least one of the shark capture events observed in the YouTube videos was eaten by another shark during the fight.

While the consequences of catch-and-release are often highly context-dependent, the implications of hooking large fishes hundreds of meters offshore, are likely to be extreme exhaustion, physiological disturbance and, on occasion, depredation.

Potential loss of fishing tackle by drone anglers is also concerning. During angling, it is common to lose tackle when terminal tackle gets stuck in rocky habitat. Additionally, tackle failure, such as line breaks, are common while fighting large fish such as sharks. Both scenarios may result in hundreds of meters of fishing line being left in the ocean which poses several threats including the entanglement of birds, marine mammals and turtles and pollution of the environment. Understanding whether drone fishing does indeed increase the amount of recreational fishing associated debris left in the ocean is an important question that needs to be investigated given the severity of the issue globally. We do however acknowledge that there are environmentally conscience anglers who do use specialised rigs that if break offs occur they only leave the hook trace in the fish’s mouth. A practise that should be used by all drone anglers. While other studies have shown that the use of drones may affect other beach animals such a birds. In some instances, entire colonies of breeding shore birds have abandoned their nests after being harassed by drones.

An increase in drone fishing may increase intersectoral conflict between recreational fishers and other fisheries groups such as small-scale and commercial fishers that compete for similar fish species.

The privacy of individual beach users and their safety is also a concern. The increased use of drones along the sea’s shore means there are more eyes in the sky and more chance that one may fall out of the sky and injure other beach users.

Is drone fishing legal in South Africa?

At the time of writing, the drone fishing publication there was no explicit interpretation of the South African Marine Living Resources Act (MLRA 1998) that directly outlawed drone fishing in South African waters. Although drone fishing is not specifically regulated, there is other legislation that indirectly relates to the practice. For example, the national Civil Aviation Authority law states that permission is needed to drop a payload from any drone. Given that a drone fisher needs to drop a payload from a drone in order to drone fish, in theory for a drone fisher to legally fish they would need to be a commercial drone pilot and apply for permission to drop payloads from the Civil Aviation Authority. However, following the publication of our article in 2021, the South African Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) released a public notice warning recreational anglers that the use of drones and other electronic devices are deemed illegal under the South African Marine Living Resources Act (MLRA 1998). This was based on the definition of angling as:” recreational fishing by manually operating a rod, reel and line or one or more separate lines to which no more than ten hooks are attached per line. Therefore, it is clear that angling is limited both from shore and from vessels, to fishing by manually operating a rod, reel and line”. Whether our drone fishing paper alerted DFFE to the practice is unknown, but the public notice does, however, verify the MLRA’s interpretation of what constitutes recreational angling in South Africa.

References

Cooke, S.J., Venturelli, P., Twardek, W.M., Lennox, R.J., Brownscombe, J.W., Skov, C., Hyder, K., Suski, C.D., Diggles, B.K., Arlinghaus, R. and Danylchuk, A.J., 2021. Technological innovations in the recreational fishing sector: implications for fisheries management and policy. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 31(2), pp.253-288.

Kleiven, A.R., Moland, E. and Sumaila, U.R., 2020. No fear of bankruptcy: the innate self-subsidizing forces in recreational fishing. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 77(6), pp.2304-2307.

Winkler, A.C., Butler, E.C., Attwood, C.G., Mann, B.Q. and Potts, W.M., 2022. The emergence of marine recreational drone fishing: Regional trends and emerging concerns. Ambio, 51(3), pp.638-651.