The unexpected impact of a Letter to the Minister from One Ocean Hub researchers, resulting in an opportunity to facilitate counter hegemonic mapping into transgressive ocean decision making for Amathole Marine Protected Area, South Africa

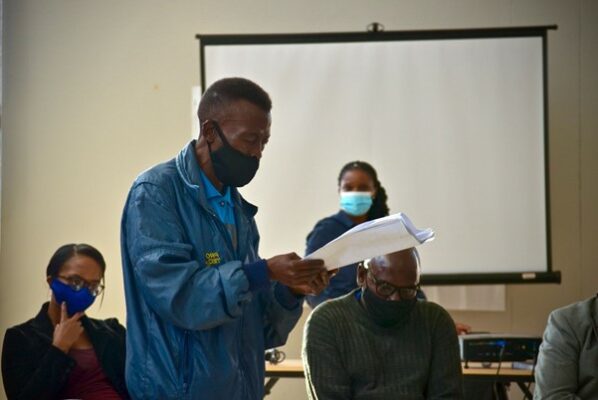

Ayanda Yekane, the leader of the Siyaphambile Small Scale Fisher’s cooperative, speaking to concerns they have with the Amathole MPA management plan. Buhle Francis, worked closely with Ayana and other leaders in assisting in the translation and interpretation of the the MPA plan.

In South Africa a growing network of small-scale fisher leaders, environmental justice organisations and researchers from the One Ocean Hub, currently called the Coastal Justice Network (CJN), has been responding collaboratively over the past two years to a range of injustices – social, environmental, economic – experienced by coastal communities and environments. We have worked collaboratively to respond to the expected negative impacts of proposed offshore oil and gas expansion, lack of participation and other human rights issues around the creation and planning of marine protected areas, policy and management failures towards small-scale fisheries, water crises in coastal communities, COVID lockdown-related limitations to public participation, and others.

One significant area of work, with noteworthy recent impact (the past 6 months) is our transgressive learning research for development aimed at linking up, mobilising capacity, and facilitating popular education processes for small-scale fisher leaders, traditional leaders, coastal youth and other coastal citizens who have been negatively affected by the expansion of the network of Marine Protected Areas. The historical and contemporary human rights issues are MPA expansion include, but are not limited to, communities being forcibly displaced from coastal ancestral land, experiencing heavy restrictions to their access and livelihood practices along the coastline in disregard of their sustainable customary practices, exclusion from MPA planning, zonation and other decision making, and culturally inappropriate and ineffective participatory processes on these issues.

Photo caption: SSF leaders and representatives, mapping their concerns and questions onto a living co-created map of the region and proposed MPA boundaries ( From Left to Right , Mr Mlungisi James Tshume Chairperson of Mlibo Coop, Mr Andile Fumba of Benton fishing Coop, Ms Nothula Ndongeni – Member of Siyazama aquaculture – Mr Ayamda Yekani Chairperson of Siyaphambili Coop and Mrs Margret Ndlakuhlola – chairlady of Kiwane Fishing Coop ). Photo: Luke Kaplan

Last year, on request from SSF leaders and civil society organisations, the CJN wrote a series of letters to the Department of Forestry Fisheries and Environment (DFFE) regarding injustices around different MPA processes in the country . We were unsure what impact these letters would have, at a bare minimum we hoped they would act as a case record to show communities’ concerns over the weak consultation practiced over MPA planning and management.

While waiting for a response from DFFE, we continued to work closely with SSF communities to:

1. Map their concerns;

2. Support efforts for SSF and other leaders to participate in online consultations around the country,

3. Document their capacity mobilization needs, and

4. Continue ethnographic research (oral histories, interviews, focus groups, archival analysis) with SSF and other coastal groups.

In March 2021, we received a response from DFFE through their partner organisation Eastern Cape Parks and Tourism Agency – ECPTA- that has been mandated to oversee the implementation of the Amathole MPA and agreed to do a follow up consultation with SSF leaders in the region. The CJN joined the consultation meeting on 29th April 2021 in Hamburg, where SSF leaders and other citizens stated their concerns, passionately described their dissatisfaction with the consultation process on the MPA management plan development to date. In response to these concerns, we noticed a willingness and openness by ECPTA to attempt to practice consultation and participation differently, moving forward. Following this, we began consultation with ECPTA and with DFFE to introduce a novel and more participatory, co-designed approach to their public consultation, which they agreed to do (an unprecedented turn in MPA consultation by a managing agency in SA to our knowledge, as they were going beyond the current legal requirements for their consultation process). Government officials agreed to return on 10th June to engage further and try out a new consultation/public participation process.

We quickly set to work, running a planning workshop with SSF leaders in Hamburg on 27th May 2021. We used novel creative methods in participatory research (Empatheatre, Public Storytelling, Counter-hegemonic mapping, transgressive learning, popular education) to translate the current draft management plan into isiXhosa (the local language), deciphering the complex language and research page by page with the leaders. We also used an ‘embodied mapping’ constellation process in which leaders paced out the draft maps and zonation of the MPA across the hall, using their bodies as reference points for land-marks and noticeable boundaries of the MPA. Based on this more nuanced and detailed understanding of the implications of the draft management plan, the leaders documented their questions and concerns, aligned to the specific page number of the management plan in preparation for the meeting with authorities scheduled on 10th of June. They also suggested an agenda for the day, saying: “if the government is coming to see us, we are then the hosts, and should therefore establish the tone and direction of the meeting”.

On the day of the meeting, the three nominated SSF cooperative leaders expressed their concerns and questioned aspects of the management plan. Although the atmosphere/agenda/tone of day was still very much in the control of government leaders, the meeting was held mainly in isiXhosa and our team were able to facilitate an interactive participatory mapping and public storytelling process. This allowed for rich, nuanced, place-based accountability to the impact of the management plan, and for dynamic dialogue – and associated tensions, to be expressed with generative engagement on both sides. This can be considered a watershed moment in MPA consultation, where past inequalities and exclusions from ocean-related decision making, could be discussed in communities’ own language and on the basis of understandable maps and documentation. As a result, the authorities at the meting expressed a commitment to include SSF cooperatives in the decision-making forum for the Amathole MPA moving forward.