The WTO’s Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies. ‘It’s good, but it’s not quite right’

After much anticipation, members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) have reached an historic Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies that seeks to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goals. In this blog post, we provide a rapid assessment of this development, after reflecting on the state of global fisheries and key facts about fisheries subsidies. We then examine key provisions of the Agreement and how they relate to ongoing research at the One Ocean Hub. While our summary is not an exhaustive account of the Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies, we pay particular attention to its prohibition of subsidies to 1) illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing; 2) the fishing of overexploited stocks and 3) fisheries on the high seas outwith the control of regional fisheries management organisations. We also draw attention to the Agreement’s provisions on special and differential treatment in favour of developing and least-developed countries as well as certain procedural and institutional features of note. We conclude by highlighting remaining issues still to be addressed at the WTO.

The state of global fisheries

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) publishes a comprehensive biennial report on the state of world fisheries and aquaculture, with the latest edition due to be released at the end of June 2022. The only such report of its kind, this report paints an increasingly disturbing picture. According to the 2020 report:

- In 2018, an estimated 59.51 million people were engaged in the primary sector of fisheries and aquaculture;

- Global fish production has reached around 179 million tonnes in 2018, with the vast majority for human consumption but 35 percent of the global harvest is either lost or wasted every year;

- In 2018, total global capture fisheries production reached the highest level ever recorded at 96.4 million tonnes;

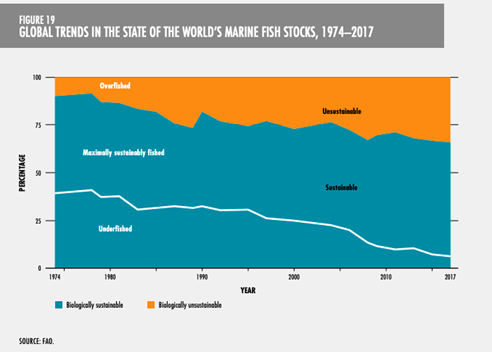

- The fraction of fish stocks that are within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90 percent in 1974 to 65.8 percent in 2017.

Figure 1. ‘In terms of landings, 78.7 percent of current landings come from biologically sustainable stocks. In 2017, the underfished stocks accounted for 6.2 percent and the maximally sustainably fished stocks accounted for 59.6 percent of the total number of assessed stocks, an increase since 1989, partly reflecting improved implementation of management measures.’ Source: FAO

These high-level statistics paint a concerning picture. Overexploitation of global fish stocks poses a risk to the human rights to life, food, culture, health, and a healthy and sustainable environment. Moreover, since healthy marine fisheries are in themselves a climate mitigation and adaptation measure by maintaining a functional marine ecosystem, there is a need to ensure sustainable exploitation of fish stocks for climate security and justice.

Fisheries subsidies

Fisheries subsidies – financial help granted by countries to help the fishing industry meet costs such as fuel – are part of this concerning picture. While not all subsidies in the fisheries sector are bad, certain forms of subsidies may fund illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing as well as encourage overcapacity, overfishing and other unsustainable fishing practices. Such subsidies risk fish stocks being fished to levels not biologically sustainable, with a report by the UN FAO, for example, underlining the concerning state of world fisheries. Simply put, overexploitation is pushing many fish stocks around the world close to collapse. This, in turn, risks the food security of millions around the world who rely upon fish as an important source of protein, with fish consumption accounting for around 17 percent of the world’s animal protein intake. Coastal communities are particularly at risk, with fish making up 80% of animal protein consumed in such communities. IUU fishing has also been linked to labour rights abuses such as forced or bonded labour and human trafficking. The International Labour Organization has reported that there are ‘strong indicators that forced labor in the fisheries sector is frequently linked to other forms of transnational organized fisheries crime’. An umbrella term for offences committed in the fisheries sector, ‘fisheries crime’ is a topic of interest to several Hub researchers (see here, here and here) consumed in such communities.

It should be clear that the more pernicious forms of fisheries subsidies primarily ‘disproportionality benefit big business’. This both creates and perpetuates inequity; ‘(b)y fueling unfair competition between large fleets and individual artisanal fishermen, they are also fostering inequality.’ These environmentally, socially and economically destructive subsidies are primarily benefiting large, industrial scale fishers. Put plainly, public money is fueling inequality, the destruction of key ocean’s ecosystems and environmental devastation. One might wonder why we are still funding nature’s destruction? Instead of supporting large-scale industrial fisheries, these monies could instead be reinvested, ‘in sustainable fisheries, aquaculture and coastal community livelihoods to reduce the pressure on fish stocks.’

In recognition of the impact of such subsidies, Members of the United Nations (UN) agreed to include in its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) a specific target for action to be taken on the more pernicious forms of fisheries subsidies. The SDGs are part of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, developed in 2015 to catalyse action over the following 15 years in areas of ‘critical importance for humanity and the planet.’ The specific target related to fisheries subsidies, SDG 14,6 directs that;

By 2020, prohibit certain forms of fisheries subsidies which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, eliminate subsidies that contribute to illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and refrain from introducing new such subsidies, recognizing that appropriate and effective special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries should be an integral part of the World Trade Organization fisheries subsidies negotiation

The 2020 date for completion of the target set out in SDG 14.6 was missed, and it was not until June 2022 that an Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies was reached within the WTO, the institution identified in the SDGs as the forum for these negotiations.

Fisheries subsidies and the World Trade Organization

Fisheries subsidies have been on the agenda of the WTO since 2001, predating the promulgation of the SDGs. The WTO is an international organisation headquartered in Geneva with 164 Members comprising both states and customs unions with full autonomy over their trade relations. The WTO acts as a forum for multilateral trade negotiations, helps settle trade disputes between Members and oversees the administration of trade agreements on diverse topics such as trade in goods, intellectual property and technical barriers to trade. While the WTO may not seem the natural home for discussions on fisheries subsidies, it already encompasses a WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM). This has broad application to a wide range of products and industries and provides a set of international disciplines regulating the provision of subsidies by governments. Fisheries subsidies are ‘fully subject to the disciplines of the SCM Agreement’ but applying these rules to regulate the more pernicious forms of subsidy granted to the fisheries industry has proven difficult. This is due in part to the fact that the SCM focuses on the trade distortion a subsidy causes, rather than other detrimental impacts on, for example, food security, the environment or on biodiversity more generally. In recognition of this, the WTO Membership agreed in 2001 to ‘clarify and improve’ the WTO’s existing subsidies disciplines as they apply to fisheries subsidies and to ensure, ‘the mutual supportiveness of trade and environment.’

Negotiations since 2001 have edged along in fits and starts. The SDG deadline to achieve an agreement by 2020 came and went without a deal. Pressure was therefore on the WTO to conclude a deal on fisheries subsidies as soon as possible, with discussions on this issue taking centre stage at the June 2022 Ministerial Conference. In the lead up to the Ministerial, it was not clear whether agreement would be reached with even the WTO Director General, Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala warning delegates to, ‘Expect a rocky, bumpy road, with a few landmines along the way. But we shall overcome them.’ Ultimately, this statement was to prove true, with the Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies agreed in the early hours of 17 June 2022, following the extension of the Ministerial by over a day.

The WTO Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies

The Fisheries Subsidies Agreement (AFS) applies ‘to marine wild capture fishing and fishing related activities at sea’ but does not cover aquaculture and inland fisheries which are excluded from its scope. The AFS draws on the WTO SCM Agreement to define its scope; in general terms, this means that only fisheries subsidies involving a financial contribution, that confer a benefit and are also specific – in the sense that they are targeted towards certain enterprises, industries or geographical areas – fall within the scope of the AFS.

IUU Fishing (Article 3)

As discussed in previous work by Hub researchers, lUU fishing undermines conservation and management measures taken by States and Regional Fisheries Management Organizations and Arrangements (RFMOs/As). This can deplete fish stocks, damage associated ecosystems, with implications for food security and human rights given the importance of fish as a source of protein for millions of people around the world. A series of international, regional and national policy and legal instruments have been adopted to prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing. The provisions of the WTO fisheries subsidy regime, in seeking to prohibit subsidies for IUU fishing, have the potential to support such efforts.

Article 3.1 AFS bans subsidies to vessels or operators engaged in IUU fishing or fishing related activities in support of IUU fishing. The idea of banning subsidies for IUU fishing is, at first sight, a strange one. It would be unusual, for example, for a Member to openly admit to providing such subsidies. However, subsidies can be granted for one purpose but then used for an entirely different purpose, such as IUU fishing. In terms of the definition of IUU fishing adopted in the AFS, the AFS text cross references to paragraph 3 of the FAO International Plan of Action to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing. While voluntary and non-binding, this Plan of Action is generally considered to provide the definitional elements of what constitutes IUU fishing. Cross referencing to the Plan of Action ‘in practice support(s) the realisation of States’ existing duties through domestic economic policy in a form that is enforceable through WTO procedures’ (source here). In other words, and as we have noted elsewhere, this provision has the potential to support States’ existing duties under the law of the sea.

Both flag states and relevant RFMO/As may make relevant determinations in respect of IUU fishing. In line with the FAO’s Port State Measures Agreement to target IUU fishing, port state Members are not authorised to make such a finding, but under Article 3 AFS may alert the subsidising Member who is required to, ‘give due regard to the information received and take such actions in respect of its subsidies as it deems appropriate.’ In relation to special and differential treatment for developing and least developed countries, a key part of the fisheries subsidies mandate, Article 3.8 AFS sets out that with respect to, ‘developing and least developed Members (and for a) period of 2 years from the date of entry into force of this Agreement, subsidies granted or maintained by developing country Members, including least-developed country (LDC) Members, up to and within the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) shall be exempt’ from the prohibition set out in Article 3.1 AFS as well as related action.

Overfished Stocks (Article 4)

Estimates suggest that a third of global fish stocks are overexploited. According to UNCTAD, the figure is higher again if depleted stocks are included (see figure 1). Article 4.1 of the AFS directs that, ‘no Member shall grant or maintain subsidies for fishing or fishing related activities regarding an overfished stock.’ The relevant coastal Member or relevant RFMO/A and ‘based on best scientific evidence available’ may under Article 4 AFS make determine whether a fish stock is overfished. Special and differential treatment is provided for developing and least developed under broadly the same terms as Article 3.

The High Seas (Article 5)

The ocean beyond national jurisdiction, also known as the high seas, are all parts of the ocean beyond coastal States’ 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). States undertake international fisheries regulation on the high seas through bi- and multilateral cooperation. The internationally accepted institutional mechanism for such cooperation in fisheries is through RFMO/As. These allow States to collectively regulate international fisheries through legally binding conservation and management measures on their members. However, RFMO/As, as an approach to multilateral fisheries management, are not without their problems. For example, there are gaps in high seas coverage by RFMO/As due to inter alia political deadlock (e.g., in the Central Atlantic and Southern Indian Ocean).

The AFS contains provisions on high seas fisheries subsidies which are important to mention here. In Article 5.1, Members are directed that none ‘shall grant or maintain subsidies provided to fishing or fishing related activities outside of the jurisdiction of a coastal Member or a coastal non-Member and outside the competence of a relevant RFMO/A.’ This provision applies to areas of the ocean not under the competence of an RFMO/A and so are not subject to any specific fisheries conservation or management measures beyond the general obligations under the law of the sea (the qualified ‘freedom’ to fish on the high seas). While the prohibition is certainly useful, fish stocks will still be at risk of overexploitation as data collection may be poor and there are no rules preventing overexploitation (i.e., catch limits, gear restrictions or seasonal closures). The prohibition in the AFS is accompanied by special care and due restraint obligations in respect of re-flagged vessels and the grant of subsidies to unassessed stocks.

Other provisions – special and differential treatment

The rest of the AFS contains further special and differential treatment for least-developed countries with Article 6 directing that Members exercise ‘due restraint’ in raising matters involving an LDC Member.’ Article 7 further provides that developing and least developed countries ‘shall’ be provided with technical assistance and capacity building to facilitate implementation of the AFS with ‘voluntary WTO funding mechanism shall be established in cooperation with relevant international organizations such as the FAO and International Fund for Agricultural Development (Article 7).’

Other provisions – procedural obligations and institutional arrangements.

The AFS also sets out a number of procedural obligations on the part of Members, with provisions to improve the notification and transparency of fisheries subsidies set out in Article 8 and Article 9 establishing a Committee on Fisheries Subsidies. Disputes under the AFS which will largely follow the structure of the existing WTO Dispute Settlement Understanding.

What the agreement doesn’t do

Our final point on the AFS is that it is unfinished. Prior to the 12th Ministerial Conference, the negotiations had focused on a third pillar: subsidies which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing. Overcapacity happens, ‘when the size of the fishing fleet and its harvesting ability or fishing power exceeds what is considered an optimum or sustainable yield.’ ‘Subsidies that, for example, that increase the number of vessels/size of vessels may promote overcapacity. Subsidies that fuel overcapacity may in turn lead to overfishing in the absence fisheries management systems. Looking at the November 2021 draft Fisheries Subsidies Text, which did contain a general prohibition on the granting of subsidies, gives us an idea of the type of subsidy likely to be considered as promoting overcapacity or which contribute to overcapacity and overfishing and provided an indicative list of the forms of payments which would fall into this prohibition’s scope. For example: subsidies for the purchase of equipment for vessels, fuel subsidies, subsidies for ice and bait, subsidies for the costs of personnel, social charges or insurances.

There is, however, an important development dimension to discussions on overcapacity and overfishing. Developing countries may wish to increase their capacity in order to pursue development objectives. In short, ‘for many developing Members (development priorities may) include building larger fleets to exploit national and high seas fisheries.’ This needs, however, to be balanced against legitimate concerns such as food security and livelihood concerns, both of which are reflected in the WTO negotiating mandate on fisheries subsidies. Developing countries are also far from homogeneous in regard to the structure of their fisheries industries; while some are largely composed of small scale fishers and artisanal fleets, others are composed of large scale industrial fleets.

Previous drafts of the Fisheries Subsidies text had attempted to deal with this issue by adopting a hybrid approach, establishing a general prohibition but also including an exception should measures be in place to ensure stock levels remain at biologically sustainable levels. Previous drafts also made provision for different forms of special and differential treatment, including; time limited exemptions for developing countries for activities within their EEZ/areas within the competence of an RFMO; exceptions for developing countries where their annual global volume of marine capture production does not exceed a certain amount (with a graduation clause also included); exceptions for developing countries in respect of ‘low income, resource-poor and livelihood fishing or fishing related activities’ within 12/24 nautical miles from baselines.

Finding a balance, however, between a general rule prohibiting subsidies and the desire on the part of certain countries for exceptions to take into account their specific needs proved too difficult during the June 2022 Ministerial. This issue was therefore left for another day, with Members agreeing to continue negotiations with a view to making recommendations for the next WTO Ministerial – the 13th – ‘for additional provisions that would achieve a comprehensive agreement on fisheries subsidies, including through further disciplines on certain forms of fisheries subsidies that contribute to overcapacity and overfishing, recognizing that appropriate and effective special and differential treatment for developing country Members and least developed country Members should be an integral part of these negotiations.’

Where next?

Should the next round of negotiations fail to reach consensus, and in the absence of agreement to keep the AFS as it is, the Agreement will be terminated by way of Article 12. This provision stipulates that such termination will occur if ‘comprehensive disciplines are not adopted within four years of the entry into force of this Agreement, and unless otherwise decided by the General Council.’ To avoid failure, negotiators at the 12th Ministerial removed the contentious issues of overcapacity and overfishing from the Agreement. In doing so, they opted for what, in effect, is an incomplete Agreement to allow these issues to be discussed at a later date. Was this a sensible decision which provides Members room for further debate and deliberation so as to reach consensus? This has yet to be seen and will of course depend on implementation of the Agreement. To that end, while it is truly an impressive negotiating feat to have concluded an agreement, the future discussions on overcapacity and exploitation will be far from easy. While the authors appreciate the importance of not ‘letting the great be the enemy of the good’, leaving this aspect of the AFS for another day may ultimately prove ‘not quite right’.

~*~

Hub researchers are working on two papers relevant to this blog post;

- ‘Current Legal Developments: The Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies at the World Trade Organization’

- ‘Casting the net more broadly? The potential for integrating human rights into the implementation of the WTO Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies’